In Sri Lanka the term tusker is

synonymous with any male elephant carrying ivory, be it large or small. Seeing

a tusker in Sri Lanka is indeed a rarity, as only a small percentage of males

on the island carry the genes to produce tusks. But in the continent of Africa

it is very different, as the African Elephant, in both Savannah species

(Loxodonta Africana) and the Forest Elephant (Loxodonta Cyclotis) the male and

female animals carry ivory. The bulls invariably are bigger and in turn carry

larger heavier tusks. But an average elephant is not referred to as a tusker in

Africa, this moniker is rather given to very special bulls who are at the peak

of genetic superiority and physical condition, enabling them to grow large heavy

ivory which weight at least 45 kg per side, and at times almost touch the

ground.

The sight of a giant bull with amazing shafts of ivory is a sight to

behold, as usually the males with the best genetic stock tend to have this

trait, and hence are physically impressive specimens. Around two to three

centuries ago such majestic bulls were found throughout the continent, these

were the prime breeding bulls and most desired by females to father their

calves and carry on their genes to the next generation. Sadly with the onset of

the white explorers came trophy and ivory hunting. Invariably the prime target were the

elephants with the biggest tusks. This systematic selection of hunting was

practiced not only by the big game hunters but also ivory traders such as Tippu

Tip who was a powerful ivory and slave trader from Zanzibar. It was one of his

slaves who killed a bull with the largest pair of tusks in the world. Shot in

the foothills of Mount Killimajaro, this bull carried a pair of ivory ,one

weighing 107 KG and the other 102 KG.

Killimanjaro Bulls Tusks- Photo credits- A.C Gomes & Co

Later with the independence of many

African nations, mass scale slaughter was rampant which further cut down on the

population of big tuskers. By the latter part of the last century only a

handful of true “Big Tuskers” remained. Historically these bulls were found in

certain regions of South Africa, Zimbabwe, Mozambique all in the South of the

continent, as well as in the East African regions of Kenya and Tanzania along

with certain regions of the Congo, namely the Lado Enclave which was known as

the prime hunting grounds for giant ivory by the Big Game Hunters of old.

Historically, elephant populations in Botswana and Namibia never produced big

tuskers of significance, as this is also depending on the type of food and

nutrition the elephants have in their habitat.

In South Africa, in the 1970’s

there were seven bull tuskers with immense ivory over 50KG per pair in Kruger

National Park. These majestic bulls were dubbed the “Magnificent Seven” by the

then Chief Warden Dr U de V Piennar as an example of successful conservation

work. These legendary tuskers roamed the various regions of this gigantic park

and passed on their genes onto the next generation. Some of these famous

tuskers are Mafunyane, Shawu, Joao, Shingwedzi and Ndluthamithi. Some of whose

ivory are still on display at the Elephant Hall in Letaba Rest Camp.

Mafunyane, one of the Magnifficent Seven. Photo Credits- Anthony Martin Hall

Elephant Hall in Letaba, Kruger Natinoal Park

Elephant hall in Letaba, Kruger National Park

These

giants all died by the end of the 1980’s but thereafter their decedents roamed

the park, with equally magnificent specimens such as Tshokwane who famously

gored and almost killed wildlife photographer Daryll Balfour, Duke who was

arguably one of the most handsome with symmetrical ivory, and Mabarule who

suffered for many years with severe arthritis which was discovered later from

his bones and was assumed to have been in intense pain most of his adult life,

and yet even these legendary bulls are no more. A new generation of up and

coming tuskers are recorded, but are yet to match the might and majesty of the

giants of old.

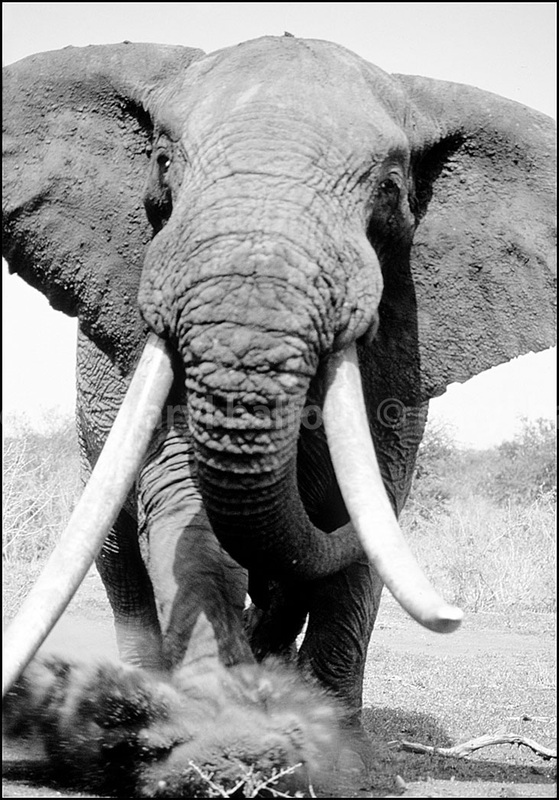

Tschokwane of Kruger National Park taken while charging and almost killed the photographer Daryl Balfour. Photo credits- Daryl Balfour

In Zimbabwe, there was the famous Chura Bull from Matusadona

National Park in the shores of Lake Kariba, who was also featured in the Clint

Eastwood movie “White Hunter, Black Heart” in 1990.

Chura Bull who starred in the Clint Eastwood movie- White Hunter Black Heart Photo Credits- Chris Worden

Moving onto East Africa, the most

famous tusker of old would have to be Ahmed from Kenya. He was arguably the

most famous tusker in the world at one time and declared a living monument by

the then President Jomo Kenyatta and provided two guards to protect him around

the clock. Ahmed roamed the forests and plains of Marsabit National Park and

was known more by reputation rather than sight. He had the most magnificent

pair of tusks which were beautifully symmetrical. Born in 1919 he passed away

in 1974 at the age of 55 years. His massive tusks weighed 67 KG each and his

skeleton and ivory is on display even now at the Kenya National Museum in

Nairobi.

Ahmed the mighty tusker of Marsabit National Park, Kenya. Arguably the most famous elephant in Africa. Photo Credit - Mohamed Amin

Looking at the current day and

age the fate of these big tuskers is very bleak. Around a decade ago there were

an estimated 40 such magnificent bulls roaming around the plains of the African

Continent. Right now less than half of that number remain and are disappearing

rapidly. Most elephants now carry small ivory and in some parks have evolved without

tusks as well, which gives a biological advantage in areas ravaged by poaching.

The demand for ivory is ever increasing, especially in the China and now due to

the lack of big bulls with large ivory even young elephants with very small

tusks are killed, all to create lifeless trinkets which are worthless in

comparison to the animal who carried them.

Out of the places known to

contain such massive tuskers, Tsavo and Amboseli come to light. Tsavo is

Kenya’s largest national park and is a giant tract of land of approximately

21,000 square Kilometers, which is estimated to contain over 12,000 elephants

in its eco system. Out of which a small handful of bulls are “Big Tuskers” with

giant ivory. Sadly some of the most well-known iconic bulls have fallen prey to

poachers, mainly those who cross from the Somali border. Bulls such as Satao

and Satao 2 both fell to the poison arrow of poachers. Protecting these bulls is

a herculean and almost impossible given the land extent, but is yet carried out

tirelessly by the Tsavo Trust which is a field based NGO, with constant

monitoring and action to protect these last remaining giants. Unfortunately it

seems like a losing battle but yet they continue to fight on.

Satao, Tsavo's most iconic tusker who was brutally killed in 2014- Photo credits- Tsavo Trust

Butchered body of Satao. Photo Credit- Tsavo Trust

Amboseli National Park which is a

much smaller eco system but yet historically linked to Tsavo via the Chyullu

Hills is home to the most studied wild elephants in the world. Research

pioneered by Dr Cynthia Moss in 1972, provided detailed findings on elephant

biology, behavior and society. She systematically named and identified every

individual elephant and their families and has records and data of elephant

families spanning many generations. Another well-known researcher and scientist

Dr Joyce Pool who started working with Dr Cynthia Moss and was fundamental in

discovering the phenomenon of musth which was once thought to be a condition

only Asian Elephant bull’s went through, but concluded as present in African

Elephants as well. Dionysus was one of the most famous bulls during the late

80’s and 90’s had beautiful wide swept ivory and was also featured in the

documentary Echo and the Elephants. Presently there are three known big tuskers

in the park. The most famous of which is Tim, who is from the “T” family and

son of Trista named by Dr Cynthia Moss, and is arguably the most famous

elephant in Kenya at the moment. His left tusk is long and reaches the ground,

while is right tusk is short and curved inwards giving him a unique appearance.

He is also a massive animal and towers above his fellow bulls and is estimated

to measure 3.4-3.5 Meters at the shoulder and weigh almost 6 Tons. The other

two living bulls are Craig and Tolstoy who is by blood Tim’s uncle but is

younger than Tim by two years and shorter in stature. Craig looks almost

identical to Tim in tusk shape, but is shorter in stature and is thought to

share the same father despite being from different mothers. Amboseli being next

to the Tanzanian border and on the foothills of the great mountain Killimanjaro

means these bulls might even be descendants carrying the genes of the giant

bull shot on the slopes of this great mountain and who holds the record for

heaviest tusks to date.

Mount Killimanjaro, seen from Amboseli National Park. Photo by Rajiv Welikala

My lifelong dream has always been

to photograph one of these iconic African Big Tuskers. With this dream in mind

I set off to Kenya in 2016 with high hopes of catching a glimpse of one of

these last mammoths of the Africa of old. I knew time was running out and it is

a matter of time that we will no longer have such awe inspiring animals left on

our planet, and hence it was imperative that I somehow see one before it is too

late. Little did I know it was going to prove harder than I imagined to find

Tim who I desired to see the most. With information received from various

sources that Tim is in the park during the time of my visit as he was in musth,

I set off from Nairobi on a long an uncertain journey to Amboseli. The park was

initially overwhelming, for someone who has never been to Africa before, the

sight of such abundance of wildlife is astounding. Elephants are everywhere and

found in their droves, from the many herds scattered across the park to lone

bulls feeding in the marshes. On my first day itself I managed to identify

Craig who was feeding deep in the marshes close to Ol Tukai. It was very far

away, but I was able to identify him from his torn ear and shape of tusks. I

was very happy at seeing him, and yet yearned to see his bigger and more

majestic counterpart in Tim. The days passed by as we kept searching the park

for this elusive bull. This is easier said than done, and I literally scanned

and observed every single elephant I could see in a 360 degree radius in order

to identify if he was Tim. One the third day at around 10.30 PM when the sun

was very bright, I caught a herd which was far away in the swampy marshes. The

light was very harsh and hence it was very hard to focus, but I noticed a

gigantic bull trailing the herd and from the shape of ivory I immediately

identified who he was. Unfortunately they were so far away and deep in the

swamps that we were unable to get close enough even for a decent photograph.

Extremely disappointed I headed back to the lodge to wait till the light gets

better by afternoon and hopefully catch a hold of him. But when we returned a

few hours later he was nowhere to be seen. I scanned the whole area in vain and

must have observed around 100 elephants one by one and yet couldn’t identify

Tim. The days passed and I had made up my mind that I will not unfortunately

see Tim, and was trying to convince myself to be content with seeing Craig. On

the last day of our tour, on the last morning safari, we set out in the park,

with no real hopes of seeing Tim, but rather maybe to try and find some lions.

As the light was getting better, I noticed a herd of elephants in the distance,

and for what it’s worth told my driver to stop the van so that I can scan and

check the herd out. To my disbelief there he was! Tim, the mighty bull who I

was chasing all this time, grazing peacefully and following the herd of females

and calves. He towered above the rest and was quietly following the herd while

keeping a distance. My heart was pounding as he approached us slowly, my hands

were shaking and I was barely able to keep them steady to keep firing camera.

His true stature and might was evident as he was mere meters from our van as he

towered above us. Paying no heed to our presence this mighty bull with the most

magnificent ivory I have ever seen, peacefully crossed the road in front of our

vehicle and continued on his way towards the marshes and the herd. It took me a

good hour or more to bring my adrenaline down, and I felt jittery with

excitement for the entire day knowing I had fulfilled the biggest dream of my

life. Also deep down I felt a sense of sadness that this maybe the last of a

noble line of giants who will cease to exist in the coming generations, all

because of the greed and negligence of man.

Tim from Amboseli. Photo Credits- Rajiv Welikala

Craig from Amboseli. Photo Credit- Rajiv Welikala

Big Tuskers are a remnant of an

Africa of old and of days gone by, and sadly will end up as nothing more than a

part of old tales and legends of a time once upon a time when mammoths roamed

the earth.

Bibliography

Africa Geographic Magazine. (2019). Africa's Big Tuskers -

Africa Geographic Magazine. [online]

Available at:

https://magazine.africageographic.com/weekly/issue-96/africas-big-tuskers/

Africa Geographic Magazine. (2019). The silent giants of

Tsavo - Africa Geographic Magazine. [online]

Available at: https://magazine.africageographic.com/weekly/issue-119/silent-giants-tsavo/

Africa Geographic Magazine. (2019). R.I.P SATAO 2 - Africa

Geographic Magazine. [online]

Available at:

https://magazine.africageographic.com/weekly/issue-141/rip-satao-2/

Alberts, E. (2019). People Just Killed One Of The Last 25

'Big Tusker' Elephants. [online]

The Dodo. Available at:

https://www.thedodo.com/in-the-wild/big-tusker-elephant-killed-kenya

BBC News. (2019). Rare 'giant tusker' elephant killed.

[online] Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-39188184

Bosman, P. and Hall-Martin, A. (1994). The magnificent seven

and the other great tuskers of the Kruger National Park. Cape Town: Human &

Rousseau.

Capstick, P. (2013). The last ivory hunter. New York: St.

Martin's Press.

Gilbert, N. (2010). African elephants are two distinct

species. Nature.

Marais, J. and Hadaway, D. (2012). Great tuskers of Africa.

Cape Town: Penguin Books.

Poole, J. and Moss, C. (1981). Musth in the African

elephant, Loxodonta africana. Nature, 292(5826), pp.830-831.

Tuskersofafrica.com. (2019). Tuskers of Africa. [online]

Available at: http://www.tuskersofafrica.com/

Ward, R. (1986). Rowland Ward's records of big game. San

Antonio, Tex. (9601 Broadway, Suite 201, San Antonio 78217): Rowland Ward

Publications.